As published in Living Blues Issue #234 Vol. 45, # 6, December 2014/unedited version by Frank Matheis

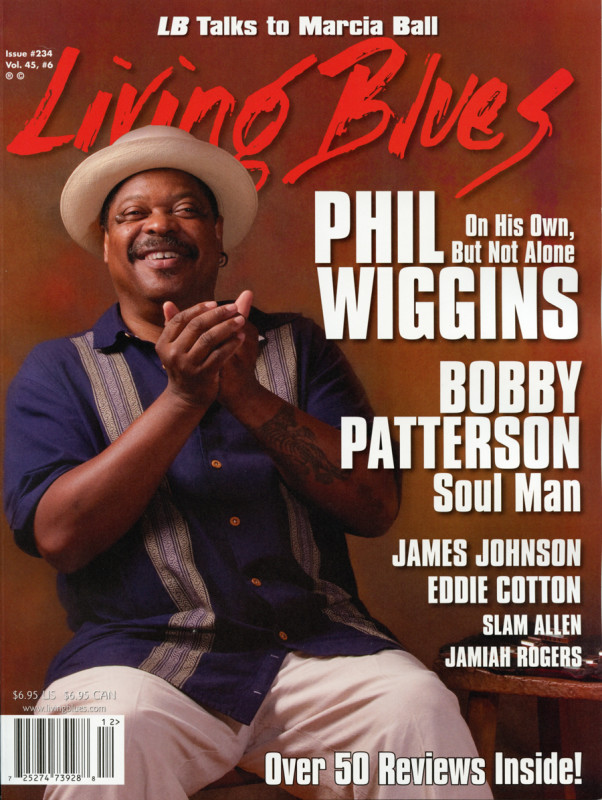

Phil Wiggins – On His Own, But Not Alone

To understand Phil Wiggins and his music, you need to understand his home city of Washington, DC. Also known as the “Chocolate City” because it is perhaps the blackest city in America, with the largest population percentage of African Americans, Phil calls it “a Southern town.” Bluesman Bill Harris, known for his pig-hollers and nylon string guitar, the proprietor of the old Pigfoot blues club in Northeast DC, used to affectionately refer to it as “Chocolate City with vanilla suburbs.” During the Great Migration of black Americans from the rural South to the cities of the North, from the early 20th Century to 1970, the population of Washington, DC exploded as many blacks headed north to seek economic opportunities and escape harsh Jim Crow segregationist laws. Like other large northern cities, the influx of southern rural folks brought along the blues musicians, but unlike Chicago, Memphis and St. Louis, the District of Columbia never developed a comparable electric blues scene and maintained its rural, country blues in the Songster and Piedmont blues traditions of the Mid-Atlantic region.

To understand Phil Wiggins and his music, you need to understand his home city of Washington, DC. Also known as the “Chocolate City” because it is perhaps the blackest city in America, with the largest population percentage of African Americans, Phil calls it “a Southern town.” Bluesman Bill Harris, known for his pig-hollers and nylon string guitar, the proprietor of the old Pigfoot blues club in Northeast DC, used to affectionately refer to it as “Chocolate City with vanilla suburbs.” During the Great Migration of black Americans from the rural South to the cities of the North, from the early 20th Century to 1970, the population of Washington, DC exploded as many blacks headed north to seek economic opportunities and escape harsh Jim Crow segregationist laws. Like other large northern cities, the influx of southern rural folks brought along the blues musicians, but unlike Chicago, Memphis and St. Louis, the District of Columbia never developed a comparable electric blues scene and maintained its rural, country blues in the Songster and Piedmont blues traditions of the Mid-Atlantic region.

The Piedmont blues is a gentle and melodic blues style native in the Carolinas and Virginia over to Tennessee, but practiced along the entire mid-Atlantic region. The rich folk tradition in the Piedmont country blues owes much to ragtime, traditional Appalachian Mountain music, African American string music, spirituals and gospel, rural African American dance music, and the early white country music of the 1930s. This blues style is characterized in part by intricate fingerpicking with alternating bass and a simultaneous syncopated melody picked on the treble strings. Blind Blake, Blind Boy Fuller, Blind Willie McTell, Rev. Gary Davis, and many others along the East Coast made this folk music style famous. Much has been said about the many blind musicians in this region, and the simple explanation is that if you were poor, black and blind in a world that offered you few other opportunities, playing music as a street busker was a way of survival. Posthumously revered, fame eluded most of these players in their lifetime and most lived an existentialist struggle that was not nearly as romantic as modern day blues lore makes it seem.

The status of the Piedmont blues, compared to its famous cousin, the Mississippi Delta blues, is perhaps best exemplified when John Jackson went over to England and was billed as “Mississippi John Jackson.” The mild mannered Virginia native gently protested, “But I’ve never even been to Mississippi,” but apparently the eastern commonwealth was considered so low on the blues-barometer that no self-respecting English promoter could have risked it.

For many blues fans, DC still does not resonate as a major blues center, but this region has historically been a vibrant and powerful source of acoustic blues. This was the home turf of Flora Molton, who used to busk on F-Street in Washington, DC. “Bowling Green” John Cephas came from Virginia, as did the wonderful country blues musician John Jackson. This is where Archie Edwards’ famous barbershop sponsored Saturday afternoon jam sessions. Bill Harris ran the Pigfoot blues club on Rhode Island Ave. in Northeast DC and not far up the road, Dr. Barry Lee Pearson, the “Professor of the Blues” at the University of Maryland, is an ever-present supporter and chronicler. Here, Nat Reese was a pillar of the blues community. Smithsonian-Folkways Records is centered in Washington and the Smithsonian Folklife Festivals have been one of the biggest gatherings of traditional acoustic blues in the world. Great currently active musicians like Eleanor Ellis, Michael Baytop, Michael Roach, Rick Franklin, the MSG trio (Jackie Merrit, Miles Spicer and Resa Gibbs) came out of this nurturing scene, as did Warner Williams and Jay Summerour, another fine harmonica and guitar duo. Musically close, but a bit further north, were “Philadelphia” Jerry Ricks, who was also a Piedmont style player and the unforgettable Blind Connie Williams, a Philadelphia street singer.

One reason for the unprecedented continuation of the acoustic blues in this region has been the willingness of the older generation to carry on the traditions. Many musicians in the center of the local blues were later teachers at the popular annual blues camp at the nearby Augusta Heritage Center of Davis & Elkins College in Elkins, West Virginia, a cultural institution of immense importance to the development of folk blues in the region. John Jackson, John Cephas, Phil Wiggins, Eleanor Ellis and others were all active teachers who taught blues workshops at the Augusta Heritage Center and other programs nationwide; and they all had local students. John Cephas was a founding member of the DC Blues Society, an organization dedicated to preserving traditional blues. This nurturing environment is still one of the most unique in the US acoustic blues today, and has contributed significantly to the progress of this genre in the region. While the blues in other parts of the country waned or became a tourist attraction, the DC blues scene carried on organically, albeit often below the radar.

Another main reason is that there was and is a central meeting point for blues musicians, young and old, black and white, and that was Archie Edwards’ famous barbershop. DC area bluesman Miles Spicer explains, “Archie Edwards had a barbershop on Bunker Hill Rd. in northeast Washington D.C. from the 1950s until his passing in 1998. On Saturday afternoons he would stop cutting hair, pull out his guitar and play blues in the Piedmont style that he learned during his youth in southwest Virginia. People came from near and far to be a part of the jams held there.”

Perhaps the greatest harmonica and guitar duo in the mid-Atlantic tradition was the duo of Sonny Terry (Saunders Terrell), a blind harmonica player who had previously partnered with Blind Boy Fuller, and Brownie McGhee, a guitar player and singer greatly influenced by Fuller. Their career spanned over four decades to the mid-1970s, peaking at the folk & blues revival of the 1960s when they reached international fame. The guitar & harmonica duo that carried on their tradition, and arguably, the true heirs to this legendary team, were Cephas & Wiggins, “Bowling Green” John Cephas and “Harmonica” Phil Wiggins. Cephas & Wiggins were the premier blues duo over the 33 years since they first connected at the Smithsonian Folklife festival in 1976. Cephas & Wiggins were Alligator Records artists and W.C. Handy award winners. They were fixtures on the festival and workshop circuit as minstrels, teachers, folklorists, storytellers and proponents of the rich African-American folk tradition. Since the passing of John Cephas in 2009, Phil Wiggins has been on his own. This is his story:

Phil Wiggins is a traditional (or natural) harmonica player, who plays only 10-hole diatonic Hohner Marine Band harps, mostly in second, cross-harp position. This style of playing allows the harper to cup both hands around the instrument and play acoustically, the same way people play unamplified on their backporch at home. When on stage, traditional players play a short distance from the microphone, without cupping the mic against the instrument. Traditional players rely only on the sounds they can naturally make with their instrument. They typically don’t carry anything other than a case of harps and don’t care what mic goes through the PA system. Every note is shaped by the hand-cupping and the breath control of the player, not the amp or the mic.

Phil Wiggins is old school, a classic Piedmont style player, but he can play anything, Delta blues, Folk, or whatever, always in the old style of the great harmonica players of the golden era: Jaybird Coleman, Hammie Nixon, DeFord Bailey, and of course, Sonny Terry. “I love Little Walter. My idea from the beginning was to express myself musically. Everybody was copying Little Walter. No wonder. He was a genius. But I just wanted my own sound. I wanted to say what was on my own mind. I have enough ego to think maybe someone will want to copy me.”

Copying Phil, a harmonica player’s harmonica player, will be a tall feat even for the most advanced harpers. His complex syncopated patterns, amazing breath control and rhythm, stylistic virtuosity, and mind-boggling solo runs do not just evoke the great harmonica players of the past, but the pianists that influenced Phil, like Meade Lux Lewis. When in the hands of Phil Wiggins, with his vast arsenal of riffs and lyrical solos, the ignoble little ten-hole harmonica becomes huge, like the noble, respectable piano. “The notes in the melody are all there. They are available,” says Phil Wiggins. He gets down not just the right hand of the piano, but then turns the harp into a percussion instrument, stretching and chugging the rhythm and doing virtual drum solos. Seconds later he turns the little harp into a full fledged horn, picking up on the tone and runs of the clarinet like Pee Wee Russell, or the early jazz trumpet like Willie Gary “Bunk” Johnson. Dr. Adam Gussow, himself a highly accomplished harmonica player and expert teacher, as well as Professor at the University of Mississippi, shared the sentiment of many harmonica players when he acknowledged, “I wish I could play like that.” Most harp players watch Phil Wiggins with astonishment simply because his virtually limitless virtuosity. He can fire off a sensational, lethally ferocious solo and a second later get into the melody with eloquent sweetness and sensitivity. Every note a siren call for the blues, Phil Wiggins wails with all the little reed instrument can stand, but with pure tenderness. He understands the power of space in his phrasing and timing – at once dramatic and powerful, yet tasteful and beautiful.

Of course, he was informed by the harmonica greats of the past, like Sonny Terry, Rice Miller, Little Walter, Big Walter and Junior Wells. All of those are great, but he didn’t copy their style. He plays own way.

Phil Wiggins is plain spoken and fundamentally kind. If there is ego, in the conventional sense, it is hard to see. He is friendly, but considering that he ranks as one of the most accomplished harmonica players in the world, ego is not inherent in his personality. He’s not a talker, not boastful; rather a good natured, quiet guy who, once he opens up, reveals over time, bit by bit, a keen intelligence and incisive knowledge of not just music, but a general wisdom. Once you get to know Phil, you find a fascinating man, an artist who has reached an impressive level of personal accomplishment, musical virtuosity and life experience.

He has paid his dues 40 years in the center of the east coast acoustic blues, with all the associated fame and existentialist struggles. Yet, there is an inherent sadness in his demeanor, not far below the mellow affability. When he first joined in a duo with John Cephas, John was 25 years his senior. Their long and highly successful partnership lasted until John’s death. During those three decades, they toured the world, produced 13 albums and achieved international acclaim. They played at the White House for the Clintons, won a WC Handy award for Dog Days of August (1986, Flying Fish) and took top billing on the festival circuit. Suddenly, upon John’s passing, Phil had to confront the impermanence of life as he lost his partner with whom he had spent most of his adult life and profession. John Cephas’ death was a dramatic loss for Phil. Mourning for friends and loved ones is difficult, losing a musical duo partner on top of it adds the harsh existentialist reality for a sideman that this means being alone and needing to start over. After John Cephas, Phil partnered with West Virginia bluesman Nat Reese, and soon after in 2012, Nat died as well, again leaving Phil in yet a second mourning and without a duo partner. Shortly thereafter, Phil Wiggins shared with LB “They are all dying on me,” with an unspeakable melancholy and sadness in his tone. Later he explained his process of grieving, “Losing musical partners is not a linear process. It is a cycle. You think you are past it, but it has no beginning and no end.”

“My parents and all the other folks we knew were all from points south. They kept their rural customs. The rules were different than for us first generation Northerners. I was born on Mother’s Day in 1954 in the Washington Hospital Center. My mother had a difficult pregnancy and we both came close to not making it. My mother had this beautiful embroidered nightgown, and that night she heard the other women patients saying, ‘That girl in the pretty nightgown, she’s going to die,’ – but we both made it. It was a miracle.”

“I had a wonderful early childhood in a home filled with music. My father was a cartographer with the Dept. of the Interior and my mother was a homemaker for me and my two brothers and sister. Both my mother and father loved music. My father was a pianist who also sang in the church choir, and his piano records introduced me to the sounds of Fats Waller, Earl “Fatah” Hines and Meade Lux Lewis. I also had a wonderful elementary school teacher who was an early musical influence. Mrs. Brooks. She was a tall black woman who played acoustic guitar. She would play Odetta, Pete Seeger and other folk songs to us. That affected me deeply. My greatest musical influence, however, was my older brother George L. Wiggins, nicknamed “Skip.” H was a guitar player and singer and I looked up to him. When I was seven, we lost our father and we became a half-orphans. My widowed mother later remarried to a military officer. He was a warrior whose stepson wished that warriors were obsolete. With my new stepfather we were transferred to Germany and the family lived on base in Manheim from 1965 to 1969. My first serious musical instrument was the saxophone, which I played in 7th grade in Junior High School. I think that a factor that surely influenced my approach to the harmonica somewhat. I picked the harp up for the first time in the 9th grade. I bent a note by accident and it was like magic… When the family returned to Washington DC in 1969, I got introduced to blues woman Flora Molton, she was a street singer who used to play on the street corner on F-Street in NE Washington, DC, which at the time was a popular shopping district for African Americans, with a wide range of stores within a few blocks. My older sister used to bring a cold drink to Flora and always made point of reaching out to her with kindness. Flora was an almost blind street singer who played in ‘Vastopol’ (open D) using a butter knife handle as a slide. She was a steady fixture in the city and played with a tin cup tied to the headstock. For many years she was a DC institution, and she soon came to the attention of the many folklorists, burgeoning blues pickers and students from Maryland, Virginia and DC. Her influence was great, including on me…By the time I was in high school, I joined the “Folk Club” and played many jam sessions with my older brother Skip. I also took notice of the Smithsonian Folklife Festivals. I also loved church gospel music. I grew up with gospel and spirituals in the church, especially in my grandmother’s neighborhood during childhood summer visits in Titusville, Alabama. On Wednesday night prayer meetings the ladies would sing a cappella call-and-response. This had a deep effect on me. But my blues epiphany came at the Smithsonian Folklife Festival at the National Mall. I heard these couple guys sit and play acoustic blues – Johnny Shines, Sam Chatmon, Robert Belfour and Howard Armstrong. They were getting down, playing like it was their own back porch. That’s when I knew– the way they feel is the way I feel. I want to play the blues. I played in an electric blues band from 1970 to ’73, the year I graduated from high school and they year when I backed Flora Molton at the Smithsonian Folklife Festival for the first time. Bernice Reagon, the gospel singer and civil rights activist got me into playing at the Smithsonian Folklife Festivals and I am grateful to her to this day for taking a chance on a ragged kid with an Afro way back then. Soon later I played a gig in Alexandria, Virginia, where I met bluesman John Jackson and his wife Cora. I’ll never forget it. He smoked Pall Mall cigarettes and carried a portable ashtray and collapsible cups. I loved the Jacksons. John was a wonderful, kind man and a great influence. He invited me to come and play with him at the Smithsonian Folklife Festival, but I didn’t take him seriously. I was so insecure. Later I saw him again and he asked me why I didn’t show up and I realized, wow, it’s real. Soon after, I was connected with the who-is-who of the blues elders in and around DC. At the Folklife festival I met and became friends with Johnny Shines, who told me stories about how the record company executives complained that Johnny sounded too much like Robert Johnson. I’ll never forget hanging out with Johnny Shines. He was an amazing guy with a never-ending set of stories. I was so in awe of him. During that time, blues pianist and singer Wilbert “Big Chief” Ellis, an Alabama native who had played with Sonny Terry & Brownie McGhee, had a band in DC called the Barrelhouse Rockers. John Cephas played guitar and James Bellamy was on bass. One night, circa 1975, I joined them for a late night jam session at Childe Herald, a popular music club at the time. Johnny Shines invited me. It was a wild night. Sunnyland Slim was in there and Sonny Rhoades. That night they asked me to sit in. After that Big Chief” Ellis asked me to join his band. It was my first major career break for me. Now I had found a permanent place as a young harmonica player with a band of established blues elders. We played at festivals all over the east coast, but mostly in and near DC. In 1977, Ellis moved back to Alabama. That’s when John Cephas called to invite me to join in a duo and ‘Cephas & Wiggins’ was born…Me and John both still had day jobs. John Cephas was a union carpenter at the National Guard Armory and I worked in a law office. Initially, we played locally on weekends at clubs and coffeehouses, but soon we came to the attention of the German blues experts Axel Künstner and Horst Lippman, who produced our first album Original Field Recordings Vol.1 Living Country Blues: Bowling Green John and Harmonica Phil Wiggins from Virginia, USA. Horst Lippmann was the producer and promoter of the famed American Folk Blues Festival. He had brought some of the greatest names of the blues over to Europe in the 1960s, and he was greatly influential in introducing the blues to English and mainland European audiences.”

In 1980, not long after the formation of the duo, Axel Künstner, a top jazz and blues music critic in Europe, declared, “Despite his 26 years he can be rated as one of today’s top Blues harp players.” Soon after the new duo made a tour of Germany and Europe with the American Folk Blues Festival and now they were on the map of the international blues community. They played the festival in 1981, along with Archie Edwards, James “Son” Thomas and Carey Bell. In 1982, they were invited back, this time with Sunnyland Slim and Louisiana Red. Their second album Sweet Bitter Blues followed in 1984, and four more in a row, one per year. By the time they were signed to Flying Fish in 1992, they were established, internationally acclaimed stars of the country blues. Their W.C. Handy award for Flip Flop and Fly was icing on the cake.

When Bruce Iglauer signed them to the legendary Alligator label in Chicago, they were a staple on blues radio, ever present on the concert and festival circuit. They had performed worldwide as cultural ambassadors for the U.S. State Department to Europe, Africa, Central and South America, and the Caribbean. The Kennedy Center sent them to China and Australia, the continent down under where they played several times. In 1988, they even performed at the Russian Folk Festival in Moscow. In Washington, they took the high honor and performed at the White House for President Bill Cinton and his family. The Washington Post review stated, “Remarkable guitar and harmonica duets. Their infectious rhythms and supple melodies combine tasteful fingerpicking with impassioned harmonica solos.” Down Beat said, “Cephas’ rich baritone singing and intricate, refined ragtime fingerpicking are a perfect fit with Wiggins’ rural-blues harmonica stylings.” LB declared “Cephas and Wiggins remain today’s premier Piedmont blues harmonica duo.”

In 1989, John received a National Heritage Fellowship guitar and Award, and after that he was considered a “Living Treasure of American Folk Music” – the highest honor the United States government bestows on a traditional artists. They also had appearances in films. Phil was featured in the cast of the movie Matewon. He had a small but pivotal role playing harmonica along with musicians of different ethnicities in a segregated coal mining camp, a short but symbolically important role showing music as a unifying force. Both musicians also appeared in the stage production of Chewing The Blues and in several documentaries –Blues Country and Houseparty.

Always dressed debonair and immaculately, wearing trademark fedora and Panama hats, they were an imposing musical presence on any stage, with a wide repertoire of traditional blues songs and originals. John Cephas sang with a warm, rich baritone. He fingerpicked his shiny new Taylor guitars, which he proudly fronted as official endorser, with his exquisite Piedmont style. Phil, the much younger sideman, heeded to the blues elder, but it was clear that his incredible talent didn’t just enhance the team – it made the duo. Like any relationship that last decades, it had its complexities and struggles, but they prevailed and persevered, reaching international fame and acclaim. They were fixtures on the blues festival circuit and produced three albums on Flying Fish and three on Alligator, plus a few gems on smaller labels, like the 1993 album on Chesky titled Bluesmen. They enjoyed a fruitful career that lasted until John’s death in 2009. Their brilliant 2008 album Richmond Blues on Smithsonian Folkways was to be their last. John’s life partner, Lynn Volpe, shared that in the last stage of his life, John Cephas said that the years he had spent playing and traveling with Phil were the best years of his life, a sentimental existentialist reflection that was included in his obituary. Their history and music lives on, but life goes on for Phil Wiggins.

Since the death of John Cephas and then Nat Reese, Phil has gigged and toured with a number of musicians, but nothing permanent has emerged. He’s performed several times with Corey Harris, later joining him on the True Blues Tour, with Taj Mahal, Alvin Youngblood Hart, Guy Davis and Shemika Copeland. “I toured Russia with Guy Davis and Samuel James. I really love playing with my longtime friends Eleanor Ellis and Rick Franklin. I also performed with Toby Walker, and Piedmont Bluz, the duo of Valerie Turner on guitar and her husband Ben Turner on washboard. Valerie was a former student of John Cephas and she is one of the fast emerging women in the genre. Lately, I have played with several DC area ensembles, including the all-acoustic swing/roots/blues ‘Chesapeake Sheiks’, with Marcus Moore – violin, Ian Walters-piano, Matt Kelly-guitar and Eric Shramek- bass. My newest band, ‘Phil Wiggins House Party’ is an exciting project that reunites the Piedmont blues with its origins as an African American dance music. The ensemble consists of Rick Franklin on guitar and Marcus Moore on violin. The band features a buck or tap dancer, usually Junious Brickhouse or Baakari Wilder.” Phil often takes the stage alone, telling stories and singing his compositions, or old standards, accompanied by just his harp.

He has taught many hundreds of burgeoning harp players and he actively continues to teach. He is now in his 23rd year as harmonica teacher at the Augusta Heritage Center of Davis & Elkins College in Elkins, West Virginia. He was instrumental in getting Blues Week at Augusta started at a time when there was no comparable program in the US. He also teaches at the Fort Townsend Acoustic Blues Workshop in Washington State, where he was the artistic director for five years. Plus, he continues to play an active role in the National Council for Traditional Arts. Talk about carrying on the legacy!

Blues scholar Dr. Barry Lee Pearson, Professor at the University of Maryland, has known Phil since 1978, “Phil has amazing auditory capabilities. He can really listen, hear and understand. He knows when to come in and when to lay back. He is an all around musician, someone who goes beyond the surface. Over the years he has developed an uncanny capacity to carry a terrific tone and a remarkable ability to express feeling. He and John Cephas were so tight, they were like one. Now Phil can hold an audience all by himself with his rare talent. He is the source. Phil has a gift to know what works and what makes the song better. He knows how to interact, how to have a musical conversation. The last time I saw him play was in a recording session with Nat Reese before he died. It just tore you up. They stripped the essence of humanity to its bare soul, it was amazing.” The recording that Dr. Pearson is referring to was the last recording session of bluesman Nat Reese with Phil Wiggins, a session that is presently sitting in the vault of a recoding studio. An active effort is now underway to revive this project and to bring it to daylight.

Phil Wiggins is searching, experimenting, and opening up to take his artistry into new directions and, in some small way, emancipating himself from the shadow of having been a sidekick for most of his career. “I haven’t found a replacement for John…maybe I never will. But I am moving forward. I always keep my ears and heart open until I can find the right connection. It was great to play with Corey Harris. Awesome! I also like doing my own music. That’s my priority– to do my own thing – to sing more, to put my own compositions in the forefront. I know that I don’t have a pretty voice like John, but my singing is good. The main thing about singing is telling a story. When I do that, things work out for me. I love storytelling and the people react well to it. They like it. That’s built my confidence to come out more with my own style, my own songs. Where this path will lead is yet undetermined, but I know this: It has been important to me to be understood. Each person hears words according to their life experience and acculturation. For people to understand each other is complex. When people need to communicate and the stakes are extremely high, poetry can happen. The fat and the bullshit are cut away. That’s when the music starts.”

In this, his next music period, we can expect some of his most daring, bravest and most innovative work.

###

The writer thanks Bibiana Huang Matheis, Lynn Volpe, Dr. Barry Lee Pearson, Dr. Adam Gussow, and all photographic contributors.

—