by Frank Matheis 2020

There are not that many straight-ahead country blues harmonica players. It’s hard to measure how many harp players follow the Chicago blues traditions of Little Walter, copying the sound by focusing heavily on the specific gear to replicate the fat amplified sound, or by wanting just the right microphone and amp combination, using lots of effects and sound distortions. It’s certainly the vast majority. Country blues harmonica players rely on their breath and hands and typically don’t cup the harp directly against the mic. They play it straight, but of course, they use a mic and amp to be heard, but they fit in with acoustic players no differently than if folks were sitting on a backporch jamming without electrification. That’s for example, how Sonny Terry, Sonny Boy Williamson (Rice Miller), DeFord Bailey and Hammie Nixon played. There are still a number of players carrying on this noble tradition today, including Phil Wiggins and Grant Dermody down in Lafayette, Louisiana. Dermody has been a steady figure on the acoustic scene, a tasteful and eloquent player who elevates any ensemble he joins. The key to playing acoustic blues on the harmonica is “just right”. Not too much, not too little. When listening to the way people like Wiggins and Dermody play, it becomes clear that they come from a deeper well. Dermody is one of the few harmonica players that plays creatively and expressively. You can’t predict what is coming ten notes into the future. It’s not the same old boring stuff. Each canvass gets vibrant new colors. Every note has meaning. He knows how simplicity can be beauty, how to enhance a song and how to say something meaningful with whatever he adds to the overall song.

thecountryblues.com caught up with the longtime harmonica ace smack in the middle of the Covid-19 pandemic lockdown by phone on May 17, 2020, to let him tell his own story:

Grant Dermody: “I picked up the harmonica when I was quite young and I started by trying to make it mine. My musical path has been different than some folks. Along my musical path I’ve met great old-time fiddle players and banjo players. I met singer-songwriters that are really fine guitar players and singers. I’ve met Cajun and Zydeco players. I’ve met bluegrass players. I’ve met Irish traditional players. All along the way it has been my goal to make my instrument fit to what they’re doing musically. That’s been a really cool path. I am influenced by everybody that I want to play music with in one way or another.

I don’t sound like anybody else. I have my own style and I have my own way of incorporating my instrument into this very old, very beautiful, very powerful form. I’ve also been around some of the most amazing blues players that were alive while I’m alive. I had a chance to hang out with them and learn from them and learn about what you need to bring to the music in order to really make it come out and be what it’s capable of being. In some ways, I am channeling what I’ve learned from them, and I’m also bringing my own voice to the forum. That’s the deal. I understand what the difference is between acoustic blues and electric blues.

I grew up in Seattle and I started off as a drummer. When I was 18 I discovered that my father played harmonica earlier in his life, in World War II. He was a violinist. He went to Holy Cross College in Worcester, Massachusetts, and he played in a big band there. All through the Great Depression he was taking violin lessons. When he was in the Navy in World War II, there wasn’t room on the boat for a violin, so he picked up a chromatic harmonica and started playing. He had a really good ear for melody and was a pretty musically, but I never heard him play around the house when I was growing up.

When I was 18 I moved to Alaska and my dad was living up there, working for the university, and he got me a harmonica in the summer of 1976. He tried to show me some stuff, how to get single notes and such. There was a guy in town who worked for the local community college who knew how to play, how to bend notes – something beyond just getting single notes. This was in Fairbanks, Alaska, 1976, right during the pipeline boom. There was a ton of money, there was a dozen places to hear live music on any given night in a town of 60,000 people, including the Air Force bases and the Army bases. There was music everywhere – people were creating and doing all kinds of cool stuff. I started sitting in with anybody who would let me sit in. and I did that for a while.

When I came back to Seattle and I heard Kim Field play in a club and he was far and away the best player around and he had that Chicago sound, he had that tongue-blocked vamping sound. He had huge tone and I started studying with him. He was a great help – he’s still a really good friend and somebody I talk to about harmonica quite a bit.

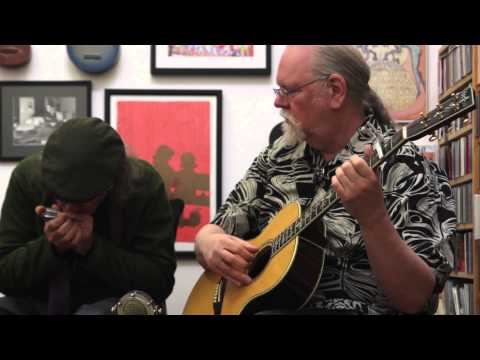

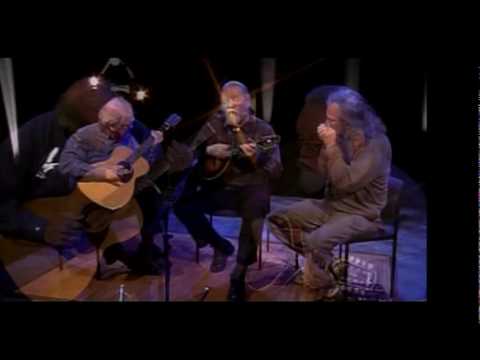

(To play harmonica well) the first thing is rhythm. If you are in an electric, Chicago style blues band, it’s helpful if you can play strong rhythm; Kim Wilson does it beautifully, but it isn’t required of you. You need to be able to hold a groove down while the other instruments are soloing. The rhythm section can hold the rhythms down and you can just play lead and sing and do whatever else is your role is in the band. If you’re in an acoustic duo, and it’s just you and a guitar player, or maybe a guitar player and a mandolin player, you need to hold down the rhythm. I’m in a trio with Orville Johnson and John Miller, and I’m also in a duo with Frank Fotusky. In that configuration, you need to be able to hold a groove down while the guitar player solos or while the other person solos. You have to understand what’s going on around you and, because you’re not amplified. I think with any kind of music that you’re playing, it doesn’t matter what it is, your job as a musician is to serve the song, and so what the song requires with acoustic music is different than what the song requires with Chicago style amplified blues. It’s a different feel, it’s a different groove, it’s a different energy, and you have to be able to bring that. That’s the deal. You’ve got to be able to play rhythm and also take inventive solos, and that is much more of a necessity with acoustic music. I back off of the mic so that I can use my hands to full advantage.

There were great moments playing when I was touring with Eric Bibb – that was really fun. I was wonderful meeting Dirk Powell and doing two records with him – those have been huge highlights. There’s been so many times playing with really great people. You’re on this musical path and different things arise, and cool things happen. I’ve been really lucky that I’ve been able to play with great people and I’ve gotten to hang out with great people and learn. I have toured with Frank Fotusky, from Tom’s River, New Jersey. He’s now living in Portland, Maine, and we’re just completing a record that we’re going to be doing some touring behind in – well, as soon as touring happens again. We’re not quite done recording, but it will be out before the new year. The record that Frank and I are doing is dedicated to John Jackson.

I love playing with Joe Filisko. We do harmonica duets, and he’s really well versed in old-school harmonica. He’s always a blast to play music with. He makes my harmonicas. I want to give him a shout out about that. I normally play Hohner Marine Bands. I need the wood. The wood sound is just a completely different sound., I get to have the wooden comb and it’s an instrument that’s customized to how I play by Joe Filisko. That’s what I use.

From a harmonica standpoint, I got to hear James Cotton live –just a few feet away from me. I got to hear Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee twice live. Sonny Terry and James Cotton were the first live harmonica players that I heard that had that huge sound that were rhythmically great and really inventive soloists and they made the harmonica sound like it was going to explode. That’s what I wanted, to be able to do that, to get that sound. Kim Field helped me find that sound when I was taking lessons from him. I was essentially influenced by early James Cotton, Sonny Terry, and Kim. From recordings, I started getting into Walter Jacobs and Walter Horton, and then DeFord Bailey, Hammie Nixon and Peg Leg Sam. Then Kim Wilson – I really started paying attention to what the Fabulous Thunderbirds were doing and then followed his career after that. I started getting into Charlie Layton and chromatic harmonica, listening to what those guys were doing, to old-time harmonica players, like Mark Graham, and Irish harmonica players. I’m always listening to how somebody else approaches the instrument, and not necessarily to incorporate that into my own thing but just because it’s fun to hear what people do that’s different than what you do.

If you go to a blues festival, during a typical two-day festival there might be two acoustic blues acts, and everybody else is playing either electric blues or rock ‘n’ roll that sort of sounds like blues. There are not that many people playing acoustic blues. It’s an art form and a beautiful musical tradition that I’m trying to keep going. The most important thing to John Cephas was the music would survive beyond him. I’m one of the people that’s trying to keep that happening.

In this particular time that we’re in, when we’re in the middle of dealing with this virus –we’re also in a time when there are many forces trying to divide us and tell us that we are different from one another, and you know in some ways they want us to be antagonistic towards one another. The music that we have, that’s blues, it talks about what everybody goes through – it talks about love, loss, about perseverance, about a spiritual centeredness that gives you the strength that you need to keep moving. All of that is what brings us together and helps us define what it is that we are trying pushing through. Now more than ever we need the blues.

I love to teach people how to find their voice on the harmonica, and I’ve done that a lot in – so different blues camps – like Blues Week at the Augusta Heritage Center in Elkins, West Virginia and at Centrum in Port Townsend in Washington. I was getting to hang out with John Cephas and John Jackson, Algia Mae Hinton, John Dee Holman, Louisiana Red, Ethel Caffie-Austin and Delnora Reed– just getting the chance to really hang out with older bluesmen and women and learning from them about the music, about just moving through life as a musician. My two biggest mentors are probably John Cephas and John Jackson, and I got to be really good friends with Phil Wiggins. It’s great to have a harmonica colleague to bounce ideas off of and stuff like that. All of that was really cool.

The best advice I can give to up and coming players is that you need to understand where tone comes from, to make the harmonica sound good, and you need to do that in your own way, because nobody else can be you. You have your own instrument, which is your body. You need to open up and relax. Most beginning harmonica players don’t understand that you need to relax into playing well. The other thing is it’s essential that you have your own voice. Yes, learn songs off of records, but don’t play what you learned off of records on stage. You have to have your own ideas and your own voice. It’s your story. This music is very personal, and you have to tell the truth and you have to get underneath it, and you have to do it with your own voice. And that’s what a lot of people starting out don’t understand.”