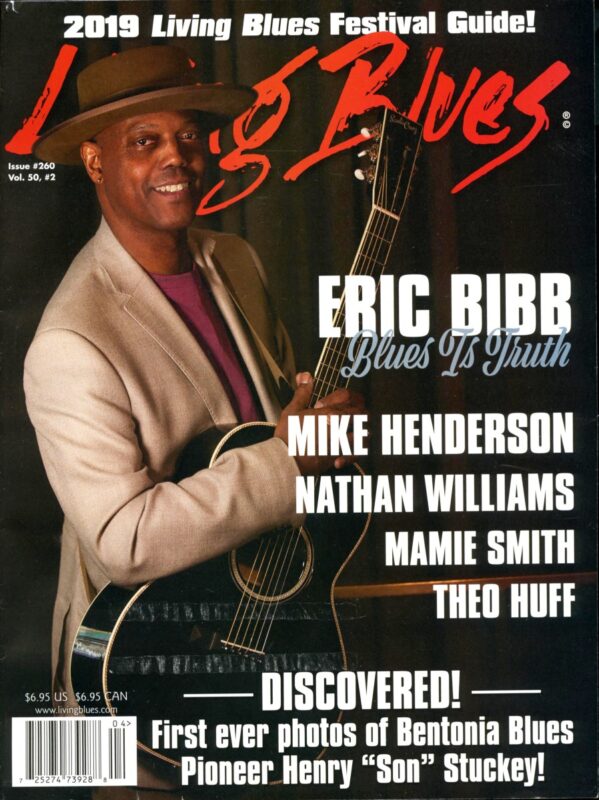

This is the unabridged article that was published in Living Blues magazine as “Eric Bibb – Blues is Truth”(Cover story. Living Blues issue 260. Vo 50, #2, April 2019.)

By Frank Matheis 2019

We live in undeniably turbulent times. You know why.

The question for thinking artists is how to react. Eric Bibb, acoustic bluesman and folk-musician, is one of the most significant singer/songwriters in the acoustic blues genre today. His voice is pivotal, not just for the continuation of blues as a relevant musical form, but, as a bold, emancipatory artistic force. His song lyrics have entered into the realm of the literary in the tradition of the blues vocabulary of writers like Amiri Baraka, Huddie Ledbetter, Big Bill Broonzy and James Baldwin, taking on the difficult thematic of slavery, Jim Crow violence and oppression, injustice, migration and the universal longing for freedom. Yet, he is not a typical protest singer.

Nor is he a typical blues singer, or, frankly, anything typical. Inimitable and strikingly singular, deeply intellectual and musically refined would be befitting. By infusing hope and dreams, daringly even “love” into his poignant lyrics, he is singing some of the most relevant, far-reaching blues, tied to the essence of humanity and embracing his listeners. When processing the messages in his body of song, it becomes evident that these are some of the most consciousness-raising, emancipatory socio-critical lyrics written today, in any genre. He writes aesthetic lyrics that are deep in philosophical essence, without bludgeoning a listener with overt preaching or propaganda. Elegant poetics without polemics. Springsteen, Baez, Dylan, and all those who speak or spoke out in song, have nothing on Eric Bibb.

Take Delta Getaway:

Saw a man hangin’

From a cypress tree

I seen the ones who done it

Now they comin’ after me

With a razor in my hand

I don’t wanna use

Got a song in my bones

Call it the blues

That short lyric embodies the new blues in its starkest, hardest expression. A man fleeing racial violence, escaping from a lynching, yet wanting to do no harm. When you listening to this powerful musical statement, Tom Waits comes to mind, citing “…beautiful melodies telling me terrible things.” Yet, Eric Bibb confidently asserts “The blues is beautiful. The blues always was beautiful, for all the blood, sweat and tears that it encapsulates, the blues has always been beautiful, because it is the song of the human spirit overcoming. And that’s why the whole world relates to it, whether they know why or not. That is the attraction.”

His songs are brilliant, compassionate statements in these reactionary times. He sings confidently, never far removed from the African American spirituals and deep roots Pre-war Blues, yet partly in the folk music realm. That combination makes him accessible to broad audiences crossing over musical delineations. Not only that, he can really sing and play, as evidenced in more than 20 critically acclaimed albums since the late 1970s. His recent works, the Grammy nominated Migration Blues and his newest album Global Griot, catapulted Eric Bibb as one of the primary songwriters on the forefront of the revival of blues as a form of sociopolitical, philosophical thematic. On Global Griot he again partners with his Malian friend Habib Koité, with whom he recorded Brothers in Bamako. They are joined by kora player Solo Cissokho and bluesman Harrison Kennedy on this journey about the griots, in what is surely a musical masterpiece.

There is a direct correlation between travel and understanding of the human condition. The more people see the world, understand similarities and commonalities, the wider their perspective, the less nativist and nationalistic they become. Eric Bibb is an internationalist, having traveled the world, connecting with African culture and music, and living in Scandinavia for decades.

His cross-cultural musical adventures and enlightened humanistic, globalist outlook embodies the old adage “music is a unifying force.” His early weltanschauung was formed by his father, Leon Bibb, to whom Eric strikes a strong resemblance in appearance as well as evocation. Leon was an actor, a folksinger with deep roots in the spirituals; and, a civil rights activist who marched with Dr. Martin Luther King. Eric took inspiration from those early influences and those of his family’s friends: Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, Pete Seeger and his uncle, the jazz pianist John Lewis. His godfather was the singer and activist Paul Robeson. Eric Bibb carried on these traditions as a creative writer and musician, achieving critical success and international fame on his own right, peaking with a series of recent masterpiece albums. Anyone who has heard any of his music knows that he is a passionate, soulful singer and a man unafraid to call for brotherly love.

As he says in his lyric, “…hoisting the banner of humanity, hoisting the banner of love.” He tears down walls – of race, ethnicity, religion and national boundaries, in direct resistance to those who divide.

Living Blues met up with the bard in New York City, where he was visiting with his wife Ulrike on the occasion of his mother’s 90th birthday:

On his musical influences

From a very early age, I was exposed to music, with a capital M –and that meant a broad spectrum that covered everything from jazz to classical to world music, folk music. My father of course was a huge influence, being active on the New York folk scene and musical theater areas were covered by his involvement in those areas. My Uncle John Lewis from the Modern Jazz Quartet, of course, was a huge influence of course in making me aware of contemporary jazz. My parents were into music in general, so that means we could hear Jussi Bjorling singing opera, we could hear folk music like shepherd songs from Auvergne. We could hear Mahalia Jackson, Big Bill Broonzy, Pete Seeger, all on the same day. So that basically prepared me for an eclectic taste in music that influenced my later development as an artist. Having anchored myself fairly early on in folk blues traditions that involved learning finger-picking styles, etc., and having built my songwriting on that foundation, I can say that musically speaking, harmonically speaking, everything that I ever heard from Ravel to Dizzy Gillespie, to Motown, to the Beatles – all of that was an influence.

On musical identity

I am grateful for the exposure I’ve had on blues stages around the world in the last three decades. I think without some kind of label as an artist in terms of “What kind of music do you play?” – I think it’s actually difficult to move forward. Unfortunately, we are all bound to some kind of marketing push if we want to be successful. You basically have to narrow your expression to a degree on recordings. I found it a little bit limiting to be considered simply a blues artist. However, that reputation is what has created a situation where my career could move forward. I think people understood from very early on though that this was a blues artist and an acoustic blues guitarist singer/songwriter who was stretching the envelope. There could be a variety of things happening under that umbrella. I think of myself as a bluesy troubadour. It wasn’t a big stretch to call myself surreal, because my function really quite easily fits into that description of being a storyteller, an oral historian – somebody who is concerned with the subtleties of history and all of that.

On songwriting

As a songwriter, I think you realize fairly quickly that you can talk about yourself, you can base your songs on your own personal experience. You can also use historical narratives as an inspiration, which I had done quite consistently. There’s a combination of personal sharing of my own journey through my songs, reminding people of historical stories, narratives that may be pertinent today because they remind us we still have things to work for and strive for as a human community. That’s been my inspiration. Things that I notice in my own travels through the songs. I also really have focused on trying to put myself in the shoes of some of my earlier blues heroes and she-roes in telling stories that I know were part of their journey but could not be openly shared because it involved too many sensitive issues that were too closely tied to their survival: stories about growing up and moving around the segregated South in the early part of the 20th century. Being too bluntly frank about those issues could get you killed. There were very few exceptions who made it to the record, meaning they had a chance to actually record some of their songs. They stepped outside of that cautious mindset. I think of people – Broonzy J.B. Lenoir, I think of Lead Belly. Those are the ones who come to mind first. There were others. But I like being a voice for some of my heroes and telling stories I know they would have wanted to share, had they been free.

Saw a man hangin’

From a cypress tree

I seen the ones who done it

Now they comin’ after me

On hope, aspiration and love

First of all, thank you for really underlining that as part of what I’m about. It’s not a word or a discussion that comes up often in the context of a blues magazine interview. Somehow that word, the “love” word, seems to somehow create uncomfortableness and embarrassment even in certain circles. You know, the blues has a real back story, and it also has a cartoonish version of what it is, because it is a commodity that has been marketed in all kinds of ways that are somehow limiting of the totality of what the blues language and culture is. There’s this pretension sometimes around the whole subject of blues, meaning that you can have blues artists who feel that they need to identify with the hardships, the reality from another era. I find that understandable. It’s an attractive, romantic kind of caricature picture of the blues, but it’s not real enough for me. I feel that the essence of blues is truth. I’m talking about when blues originally came along and was starting to be shared by recordings, etc., the early blues recordings that I grew up on, and nurtured myself on, all contained a strong element of truthfulness, of frankness – some of it really outrageously so. Even if it was an entertainment expression, it always seemed to be based on somebody’s real experience. I took that very seriously and thought, all right, I have to be true to who I am, and who I am is a child of the civil rights era growing up in an intellectual upper-middle-class environment that was far removed from the world of many of my heroes and she-roes. I had to find a way to connect to that earlier scenario and combine it with my own personal experience. The theme, the concept, the idea surrounding universal love, spiritual-oriented love, was the way I could anchor myself in my own truth and still connect to this wonderful tradition. It wasn’t something I planned, but I realized that it was something that I needed to express: claim my infinity for these teachings. I found that there was a way to write songs that included this philosophy that maybe wouldn’t work for everybody, and maybe certainly not a certain section of the blues community. This was really my calling. This was natural. This was what I should be doing.

I’m fortunate. I’m happy to be able to make a living being rather than pretending to be something. I’m being myself and I’m able to sincerely put my ideas and my philosophy and my core beliefs into my songs and find that that’s attractive to a growing number of people. I’m just really following through with the way I was brought up. I never really diverged from that real early foundation in ethical culture. A person like Martin Luther King, a person like Paul Robeson – all people who were part of my journey in one way or another were influences and I took a lot of strength from their courage and their way of claiming their allegiance to compassion and human understanding. All of that is natural to me.

On music as a unifying force

It’s a natural way for me to go forward because it reflects my journey, my experience. I’ve always been curious about one thing – music from other places. I’ve been fascinated from a very early age – about 14 – with West African kora music that you will find in the Malinke cultures in Guinea, the Gambia, Senegal, Mali. That music touched me the first time I heard it, and I basically sought it out. When I moved to Europe as a young man I found quite a few opportunities to connect with this music on a more direct level: meeting kora players, etc. I ran into – early on in my time in Stockholm I met a man named Ahmadu Jah, who is actually the father of the artist Neneh Cherry. He’s from Sierra Leone. He lent me a huge batch of wonderful records, including the famous kora duets from 1970 with Toumani Diabaté’s father. It’s called Ancient Strings, and it was a remake of that record. I was fortunate enough to meet young African musicians who made it easy for me to really delve into this music that had fascinated me from the first time I heard it in New York when I was 14 on a record. My background involved family friends from different parts of the world, and the music was just an extension of that whole orientation towards universal culture. Blending musical styles – not hodge-podge – with some serious regard for the traditions that I was learning – I found it fascinating to make my own personal gumbo built on the stock of country folk blues. I found that it was a palette with a canvas that facilitated mixing different things. I think there’s something absolutely magical about how attractive African American folk music, especially in its earliest forms, has enchanted the whole world. This has always been something that I pondered. Here you have a music that was created some hundred years ago that coalesced at that time as a style or genre that has attracted musicians from all over the world. You find people singing country blues anywhere in the world, from Warsaw to Manila to Helsinki to, you know, everywhere you look somebody is going to be able to play something that Big Bill Broonzy or Robert Johnson played. To me this local music, provincial music style that basically was a survival expression from people who were seriously, seriously downtrodden and oppressed, somehow they were able to fashion – they were given a gift that they developed and spread throughout the world slowly but surely and very quickly after technology came along, where you and blues players like Lead Belly and Broonzy traveling to Europe and Armstrong, a long time ago and basically being ambassadors for this wonderful healing energy – this music that everyone wants to sing, whether it’s gospel or Dixieland or Delta blues. This music has captivated the whole world. Interestingly enough, many African Americans have disassociated themselves with this incredible treasure and it’s coming back to America often through people who discovered it who knew someone else. It’s interesting.

On playing with Michael Jerome Brown, as one example of musical universalism

This is God’s humor. This is fantastic. You have a child from Celtic and Scandinavian ancestors growing up in Montreal, Canada who plays like nobody else who has integrated the subtleties of this wonderful language in a way that is very rare, and I am fortunate to have met Michael and to have been able to for so many years work together with him.

How music emancipates

These are hard times of great change. Music has a way of helping us through hard times of great change. It always has. Great social movements that have transformed society, whether it’s unionism or women’s suffrage or the civil rights movement or the protests movement, anti-war movement that really burgeoned in the Vietnam era – that has always been an inspiration for songs. And not necessarily just so-called protest songs. I’m a child of the ‘60s, so the whole era of protesting, whether it’s Phil Ochs or it’s Pete Seeger– that music was not the music that I gravitated to the most, but it was definitely in the mix, and there were certainly songs from that era that related personally to me, that I could really enjoy. A lot of it I felt was not musically exciting enough to really capture my attention. But there were exceptions for sure. And it was not a conscious choice or it wasn’t a pre-mediated thing: “Oh, I’m now going to sing protest songs, because the world is becoming more and more divided, I should sing protest songs.” When I was putting together the migration album, Migration Blues album, it just became natural. I made the connection between what was happening in Europe with all these refugees coming to Europe, with some of them unfortunately not making it but winding up in the Mediterranean – when that was suggested to me, I thought about it and I thought that’s definitely a rich area for exploring, but I didn’t want to become dogmatic. I didn’t want to become standing on a soapbox. I wanted to make music that was appealing but that also conveyed something about what was really happening in the world with this human tragedy that was evolving. I connected the refugees that were flooding into Europe – from Africa primarily and from the Middle East – when I connected that with the Great Migration of African Americans and my personal family’s history of thousands and millions of Americans leaving the rural South for the industrial cities of the North – when I realized it, I not only historically but actually in my own experience I am a migrant – I am an immigrant living somewhere other than where I was born – then the songs really started to flow.

Reflecting on Migration Blues

I think it’s important that if you are going to preach love, if you are going to teach love, if you are going to put it out there, wave that banner, because you believe in it and you stand for it, you also have to back it up with not just any ideas that don’t really relate to people’s reality on the ground. The opportunity for Migration Blues to actually tell some real stories and inject hope and promote the idea of compassion for a person in need, for a refugee who has lost their home, that really worked for me. That really just – and including a song by – Bob Dylan – “Masters of War” – was very natural and easy, because I thought – What is causing all of these conflicts? They are fueled by greed and aggression. But what is the material that is driving all these people – these weapons of destruction? Somebody is making these things. Who’s saying stop that? You know, people can say, “Stop coming into our country with your sad-ass stories and your plastic bags full of your belongings.” What’s the back story? Nobody is reeling against the manufacturers of these horrible inventions. I thought it was time to bring that back into awareness. Blues as a genre has not overtly been concerned with transforming society through songs of protest. But they’re out there. More than anything, the truth factor has to be included if you’re going to talk about blues. You have to talk about something that’s real –– particularly to a group of people who really need to see change and justice.

How to make cross-cultural projects like Global Griot work

I would say very important to that successful chemistry is friendship. There are many musicians who I know and have met and the particular ones that are on this album are friends. Habib has been a friend for more than a dozen years. Solo Cissokho is a more recent friend, but he’s like a long-lost brother.

It has to do with his musicality but I would say it has to do with his personality expressed through his music. And he’s a master kora player and a passionate, caring, internationally-oriented person who lives in Oslo, Norway, who has a great sense of humor but also playfulness comes through in his playing. He’s concerned at the same time with issues that I’m focusing on in my songwriting. I feel like almost everything I’ve done prior to the Global Griot recording was almost preparation for this meeting, this “Gathering of the Tribes.” I was interested in it, I started experimenting with mixing world music styles years ago, and this is the best result yet and it was natural. The logistics were challenging but the actual music making to a song really was on the easy-street. We didn’t force anything, we didn’t have to analyze anything. I’ve been aware of the modalities of the kora for some time.

I already figured out what keys, what type of harmonies worked with the natural tunings of the kora, and there were quite a few. I already worked that out. When I listen back and I think, “God we made that?” You know? Yeah.

On spiritualism in his music

It’s difficult to put into a few sentences, but I can say that having grown up in a household that basically was not practicing any set religion, but was definitely rooted in African American expression of Christianity – my grandparents we went to church when I went to visit them in Louisville, Kentucky or whatever – not when I was growing up in New York – my parents were not church attenders, but they certainly grew up attending church. We had no rigid religious rituals at home, but we were very much aware, because of the music, the gospel spiritual, negro spirituals that were in our home. We knew where we came from. And that music, the spirituals and the gospel music, particularly the earlier stuff that I heard – Mahalia and before – Roland Hayes and the songs that my godfather sang – that whole wonderful sorrow song tradition – you know, negro spirituals – resonated deeply with me… Yes, I believe in the creator. I believe in a loving force called –whatever. I wanted to let people know that I also attach to a tradition of expressing Christian values. It gave me a lot of thought time, this whole, “How do I do this? How do I sing songs that let people know I believe in the universality of the human tide, I believe in the creator, I believe in the keynote called love that I believe despite appearances is basically ruling us and our world?” Finding a way to express these things in songs has given me a way to explore deeper my own spirituality and discover what I really want to say – not from a dogmatic point of view but from a personal point of view: what do I really believe in? Am I courageous enough to stand for it?

On affecting people with his music

I am amazed when I get comments through social media when people tell me that a song actually helped them through a dark period, changed their life even, helped their family – I think what a blessing to have been prepared for what I do the way I was prepared growing up with the people I grew up with and the family I grew up with, exposed to the people I was exposed to. What a blessing. This to me is an indication that often it’s time to step out of the way in terms of the ego and just realize, “You were prepared, Eric, for a certain calling, spreading a certain message.” And the believability part of it has to do with the fact that it’s not an add-on; it’s an evolution of where I’ve been coming from forever. And I’m channeling. I’m channeling something that’s real and universal, and I have a personal twist, because everybody can collaborate with the divine and put their personal spin on universal ideas…The more people affirm what I am doing is meaningful, the more I feel responsible to the job, feeling that it’s essential for me to keep it real, keep it real…I’m happy to be connected to my dad, happy to be my godfather, happy to be connected to Pete Seeger, happy to be connected to Lead Belly, to Odetta, to Broonzy – to be in that band – Gary Davis – to have met these people and to feel like I’m somehow been able to carry on something that’s bigger than all of us individuals. That’s an amazing blessing – amazing. I’m amazed.

What he most wants the world to know about him

… I don’t know if I’ve ever actually succinctly just said something like this: you know, I came into this life, this world, this time around as an African American, and an African American who certainly experienced all the horrors – on some level or another – indirectly or directly – of the poisonous culture of racism that we have not been able to let go of here in America. But having had opportunities that many people – not just African Americans but many people don’t have – traveling to Europe when I was 12, having a 13th birthday in Kiev, being able to visit foreign countries at an early age and understand that I was not simply an African American black person, a Negro, but as a human being. Having been exposed to that idea early on, and having it successively being affirmed by all my experiences, I feel that I want to tell the world that we are a family! The concept of races – three or four races – is a social construct. This is not biology, this is not reality. There are genetic pools that are diverse and all of that, but we have much more in common, and we are actually not divided by race. This is false. I would just like to let people know that I have personally experienced my own humanness beyond my own blackness. And I think every person, whether they are a so-called person of color or not, needs to – or deserves to experience themselves as simply a member of the human tribe beyond their identification to any specific culture. There are good, valuable things in every culture that we should share, but we really need to relate to ourselves as brothers and sisters, not wearing our culture as a badge that separates us from them. This is what I have to say.